Diane Cowan, a private marine biologist, researches the lobster population on the shore of Orrs Island. |

By Bonnie Washuk Used with permission. ORRS ISLAND - Working in a cove at low tide one recent morning, lobster scientist Diane Cowan lifts up some rocks. She quickly finds two young lobsters, each less than two inches long from stem to stern. "Hey, little guys," Cowan coos as she picks them up with gloved hands and places them in a plastic container, ignoring the tiny tails flipping madly. |

| After Cowan canvasses a strip of the shore and collects more than a dozen lobsters, she tags each one so they can be tracked. Then she speaks into her tape recorder, noting their size, health, characteristics and gender. Finally, she releases the lobsters, putting them back where she found them, snug and safe under the rocks to prevent them from becoming sea gull lunch.

The data Cowan is collecting will become part of her research on the health and size of the juvenile lobster population in this southern coastal area. Cowan pauses briefly from her logging and recording, and glances at the nearby homes on shore. While she's concerned about the threat to the lobster fishery posed by overfishing, she sees another threat. "My biggest concern for lobsters is coastal development: their loss of habitat (and) non-point sources of pollution," Cowan said. She lifts another rock. Its bottom side is covered with a white filmy substance. It's bacteria -- pollution from humans. Cowan didn't see the smelly white stuff five years ago. "I've noticed habitat deterioration, habitat degredation and habitat loss," Cowan said. "There's increased sedimentation, more fresh-water runoff." Cowan has started seeing something else she didn't see five years ago: dead lobsters. "I started finding them in 1995. It's usually in the fall. It's not a huge proportion, but I didn't see them before." |

|

| The dead animals are between 2 to 4 years old. "On the outside they look fine. I don't know why they died." It would be hard to find out why, she said. "If you did an autopsy and opened them up you couldn't determine the causes of death because they're teeming with bacteria because they degrade so fast."

But Cowan has her suspicions: She believes they died from pollution. There's a connection, she believes, to the white substance on the rocks that she didn't see a few years ago and the advent of the dead lobsters. "I don't know where the demise of the lobster industry will come from," Cowan said. "My fears are that it won't be the lobstermen. There are so many external factors. To me the big one is coastal pollution. These guys are hardy creatures. They're masters at settling in different kinds of area. They're little survivors. But I worry about how long will it be that it is safe for us to eat lobsters. There are already dioxin warnings about eating the tomalley (the liver of the lobster). How long will it be before we get warnings about what's in the muscle tissue?" |

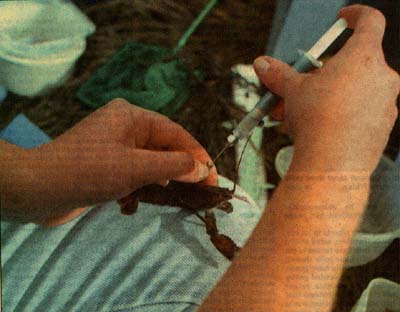

Biologist Diane Cowan uses a hypodermic needle to inject a tiny metal tag into the claw of a young lobster. The magnetized tag, about the size of a grain of sand, allows Cowan to document the growth, movement and health of individual lobsters. |

| Cowan, who has been researching lobsters since 1983, is considered a leading expert on lobster reproductive biology, behavior and on intertidal lobster distribution patterns and ecology. She donates her time to a newly formed group called The Lobster Conservancy, a non-profit group dedicated to protecting the lobster fishery, "to make sure lobsters are always around for fishermen and the rest of us."

A former researcher and teacher at Boston University and Bates College, she is now conducting research through grants, and supports herself by waitressing at Cook's Lobster House. To protect the industry, Cowan would like to see all of Maine's remaining undeveloped land on the coast be put into conservation easements. "That's totally unrealistic," she acknowledged. "But more realistic is to protect the headlands that drain into the coastal area." Maine now has a 75-foot setback requirement for coastal development. "I don't think that's enough," Cowan said. More needs to be done to protect the wetlands and shoreland, she said. The shore serves as a lobster nursery; it is where baby lobsters grow in the warm months. During the cold months they move to deeper water. It is not until a lobster is about 6 years old that it moves out to deeper water year round. The same kind of laws that have been passed to protect clams need to be passed for lobsters, she said. "Every town ordinance that says 'clams,' 'lobsters' should be added to the regulation." Also needed, she says, is more research. For instance, Cowan said it isn't known where lobsters breed or where their "maternity wards" are, and not a lot is known about the juvenile population. "The only monitoring done is on the lobster catch. But that doesn't tell you about the population," she said. "There are still huge gaps in our knowledge. One gap is how the littlest ones start out as larvae. ... One would think an organism fished so heavily would be better understood." If more was known "we could better predict the future of the stock, and help fishermen," she said. Cowan wants lobsters to be around for a long time, for fishermen to harvest and for people to eat. She says she doesn't want to see the industry disappear and convert to fish farms. Nor, she says, does she want to see independent fishermen who work for themselves and own their own boats be lost to corporate chains. Education, she said, is one way to ensure Maine continues to be identified as the state with so many lobster fishermen. If more Mainers realized that the shore serves as a nursery for lobster, for instance, more steps would be taken to protect it from pollution, Cowan said. One goal of The Lobster Conservancy, which asks for public donations through its "Adopt A Lobster" program, is education. "Everyone, especially lobstermen, should make an effort to learn," notes Matt Waddle, a Harpswell fisherman who is a member of the group. "We've got a lot of people working on the resource who don't know about how it reproduces, how we end up with another new batch of lobsters. It's true with anything: If we understand what's going on we're better equipped to protect it." |

|